Are Solar Powered Yachts the future?

Harnessing the sun’s free, abundant and eco-friendly power has been a long-held dream but is yet to become a concrete reality. Even though the first practical solar cell was invented more than 60 years ago, today — when awareness of climate change and the need for green energy has never been higher — PV solar power accounts for just 3% of the world’s energy supply.

However, in 2014, the International Energy Agency predicted that the sun could become our largest source of electricity by 2050, accounting for a sizeable 27% of the global supply. Since then, the outlook has been sunny; in 2016, new solar capacity soared by 50% worldwide.

Leading brands are getting involved in the cause, helping PV systems make the transition from niche innovation to must-have design component. IKEA made solar panels available to the public in 2013, then branched out with solar battery packs, made in collaboration with Solarcentury. In 2016, tech entrepreneur Elon Musk bought solar panel-maker SolarCity, and has since developed the Solar Roof, in which durable, tempered glass roof tiles with invisible solar cells are integrated with a battery, allowing stored energy to be used in the home.

The real driver for mass adoption will be financial and the prices of solar power are falling. “In many parts of the world, such as parts of southern Spain, solar power is now as cheap to generate as it is to buy power from the grid,” says Dr Piers Barnes, a lecturer specialising in solar cells and energy conversion systems at Imperial College London.

More regions than ever before are involved with solar enterprises. Saudi Arabia revealed plans for an enormous €162 billion solar power project to be built in the Saudi desert which will triple Saudi Arabia’s electricity generation capacity.

Solar technology is easier to produce. “The biggest development over the past five years is a massive explosion in research into hybrid perovskite materials,” says Dr Barnes, referring to cells that are soluble and so can be easily sprayed onto a surface, bringing costs down and opens up possibilities. Manufacturer Tata Steel is working in Wales on producing panels for use on roofs by spraying solar cells onto building materials.

Solar Powered Yachts

These advancements have also filtered through to yachts. Back in 2010, the launch of futuristic-looking MS Tûranor PlanetSolar (now named Race for Water) broke records as the largest solar-powered boat in the world — and went on to break more two years later, when it became the first solar-powered electric vehicle to successfully circumnavigate the globe. Costing €15bn to make, the 31m vessel is built with 537m2 of solar panels and some 8.5 tons of lithium-ion batteries, allowing PlanetSolar to reach speeds of 19km per hour.

Energy Observer is another impressive vessel that utilises a blend of renewable energies. Launched in 2017, the ex-racing catamaran draws on solar panels, wind turbines, electric motors and a traction kite to produce eco-friendly hydrogen power, which is significantly lighter than conventional fuel, allowing Energy Observer to slice through the waves at speeds up to 78km per hour.

“Solar panels were significantly more expensive in the past,” says Michael Köhler, founder of Silent Yacht, the company behind the solar-powered Silent Yachts series. “Now a panel that produces one kilowatt a day can cost €100-€150.” Vessels are now evolving to keep up, such as changing their shape. “Boats used to have rounded roofs, yet over the past couple of years, more boats have roofs that extend at the back by several metres to protect them from the heat and to use for solar panels.” He adds that batteries’ cost, size and weight have halved since 2009, making solar increasingly viable.

Another company, Soel Yachts, has developed a solar-powered catamaran that can feed energy back to the grid. On the water, solar power does have its limitations. “We have a solar electric speedboat that goes up to 30 knots, but the question is, how long does the battery last at that speed?” says Soel Yachts’ Linda Brembs.

The question of storing power is also a concern; as sunlight is intermittent, adequate power needs to be available even in darkness. As Dr Barnes puts it: “The two go hand in hand — localised power generation needs batteries so you can use the solar power when you need it.”

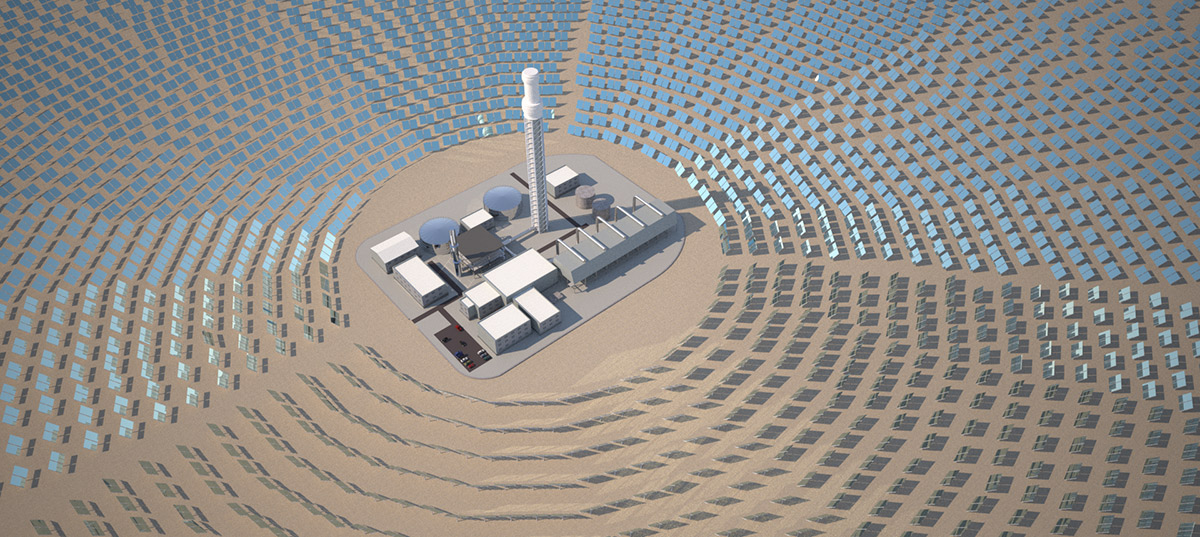

Although solar panels still dominate the sector, another system, concentrated solar power (CSP), comes with built-in power storage capacity. It generates energy by using mirrors or lenses to concentrate sunlight onto a small area, but costs can be steep and the technology can only be used in parts of the world with high direct sunlight.

UK-based energy company TuNur aims to be the first to generate renewable energy on one continent and transport it to another: a large-scale CSP farm in southern Tunisia will generate energy and transmit it across the Mediterranean Sea to Malta and beyond. “The basis of our project was that the Sahara is very close to Europe and with CSP you have storage benefits,” says Daniel Rich, TuNur’s Chief Operating Officer. “In Europe, you have a huge demand [for renewable energy] because of the de-carbonisation strategies of many countries, the need to replace coal and nuclear plants and the electrification of transport.”

Another issue is space. While solar panels are less obtrusive than other green energy initiatives, such as wind farms, large-scale solar power generation will require sizeable solutions that can integrate into our existing landscape.

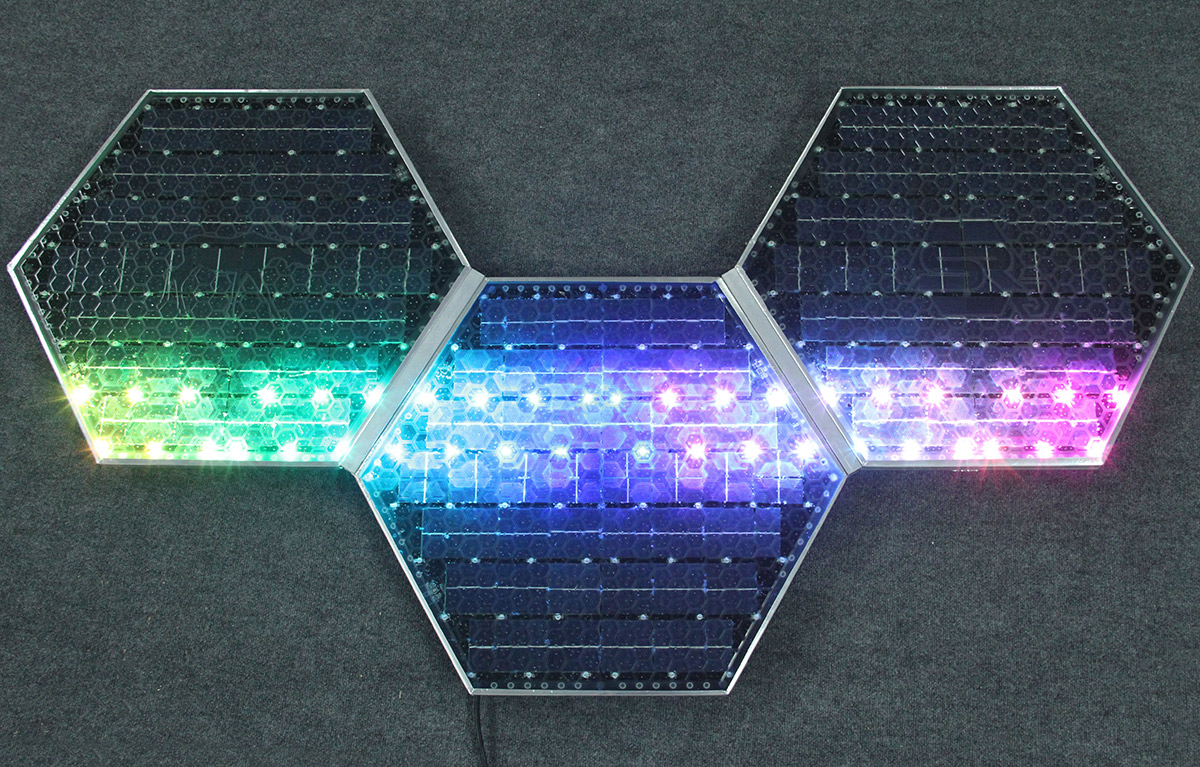

Transparent solar panels provide one solution, rendering the huge expanses of glass in every city as a potential suntrap. In 2017, tech start-up Physee fitted 30sq m of its PowerWindows — fully transparent and solar-power-generating — into the headquarters of the Netherlands’ biggest bank, Rabobank, in Eindhoven. Solar panels have been installed on greenhouses, allowing land to be used for both power generation and agriculture at the same time.

Other space-saving solar technologies may take longer to go mainstream. In 2016, Anglo-French company Colas opened the first solar road in France using innovative PV panels only a few millimetres thick. American company Solar Roadways is developing a transparent driving surface with solar panels underneath, but as yet such panels for both projects are hugely expensive. Elsewhere, French energy company Ciel & Terre International has installed an experimental floating solar farm off the coast of the UK. The Japanese Space Agency is trying to send solar panels into space to be nearer the sun to capture more concentrated power, while a team in Finland is working on a 3D-printed tree that will store solar energy in its leaves.

Go back

Go back