Growing Up: Green Architecture

The Evolution of Green Architecture

The first technology to bring the outdoors inside was glass. The age of exploration brought exotic plants into the domestic realm for the very first time. The Victorians had a passion for houseplants, aquariums and conservatories, the latter evolving into elaborate constructions of glass and steel that were the precursors to the age of modernism in the 20th century. Yet it wasn’t until the post-war era that the synthesis of natural forms with the hard edges of modern architecture started to move into the mainstream. Ultimately, there arose a whole generation of architects who were finally able to transform the idealism of the 1960s and 1970s into functional modern buildings — buildings that heralded a fusion of technology and innovation with the vision of living, breathing cities with vegetation at their heart.

Green architecture began as a reaction against the austere, technocratic aesthetic of hi-tech, which was increasingly seen as machine-age architecture that rejected not only natural forms, but also the actual integration of plants themselves. The “bible” of green design was Robert and Brenda Vale. “The Autonomous House”, an esoteric but forcefully argued advocacy for low-energy living, driven by a desire to minimise waste and energy use, and design for the best use of the sun, wind and rain. Today, low-energy design thinking is codified into almost every building specification, but back in the 1970s these ideas were decades ahead of their time.

The vertical garden of CaixaForum Madrid at its creation in 2007 – ©Cillas

Living wall Paris-Vertical Garden made by Patrick Blanc on the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris, France, Europe. © Soma

Patrick Blanc

Using the latest glazing technology and computer-controlled passive ventilation, a competent architect can ensure that even the sleekest modern skyscraper uses the least possible energy. The next step was to create a visual expression of this “green” architecture. The pioneering work of architects such as Patrick Blanc introduced the concept of a living “green” wall, a vertical garden that could be installed on an inside or outside façade and instantly transform the space into an oasis, a refuge from the harsh surfaces and forms of the city. Blanc’s installations are fed by a clever web of piping and soil-supporting structures and function as everything from centrepieces in corporate spaces to living, breathing, life-enhancing elements that transform a mundane outlook into a verdant and inspiring one.

Stefano Boeri

Other architects are going further. The Italian designer Stefano Boeri has introduced the concept of the “vertical forest”, first with a dramatic pair of apartment buildings in his home city of Milan. Completed in 2014, the two towers of 110m and 76m contain a total of 900 trees and 20,000 different plants, all set in the big, cantilevered planting boxes that are irregularly placed on every floor of the building. Just as the high-rise apartment building radically increased the number of people who could live on a given plot of land, Boeri says that each tower is equivalent to 7,000sq m of forest, helping to improve air quality, as well as providing habitats for wildlife and a surreal outlook for the upper-floor residents, who view the cityscape through a canopy of leaves.

Growing further, Boeri has been working on The Nanjing Vertical Forest project since 2016, which features two towers covered in greenery, aiming to combat the environmental and climate crisis through architecture and planning. The towers, reaching 200 and 108 meters in height, are home to over 800 trees and thousands of shrubs and plants, absorbing air pollution and contributing to biodiversity in the region. The project focuses on integrating nature into urban spaces, promoting sustainability, and enhancing the well-being of the community. With a mix of offices, commercial areas, educational spaces, and a museum, the complex represents a new vision for green architecture, aspiring to create more liveable, sustainable cities while minimizing land consumption.

Stefano Boeri’s vertical forest, a pair of dramatic apartment buildings in his home city of Milan

Eden, Singapore ©Hufton+Crow

Heatherwick Studio

The innovative design of the apartment building in Singapore’s Newton district by Heatherwick Studio, 2019, represents a groundbreaking approach to green architecture. Inspired by the concept of a ‘city in a garden’ and the lush tropical setting of the area, the studio’s design integrates nature into urban living in a remarkable way. By elevating the apartments above a densely planted tropical garden, and incorporating extensive greenery throughout the building, residents are surrounded by natural elements while enjoying the benefits of apartment living. The building’s unique layout and abundant green spaces not only provide stunning views and privacy but also contribute to a tranquil and sustainable urban environment.

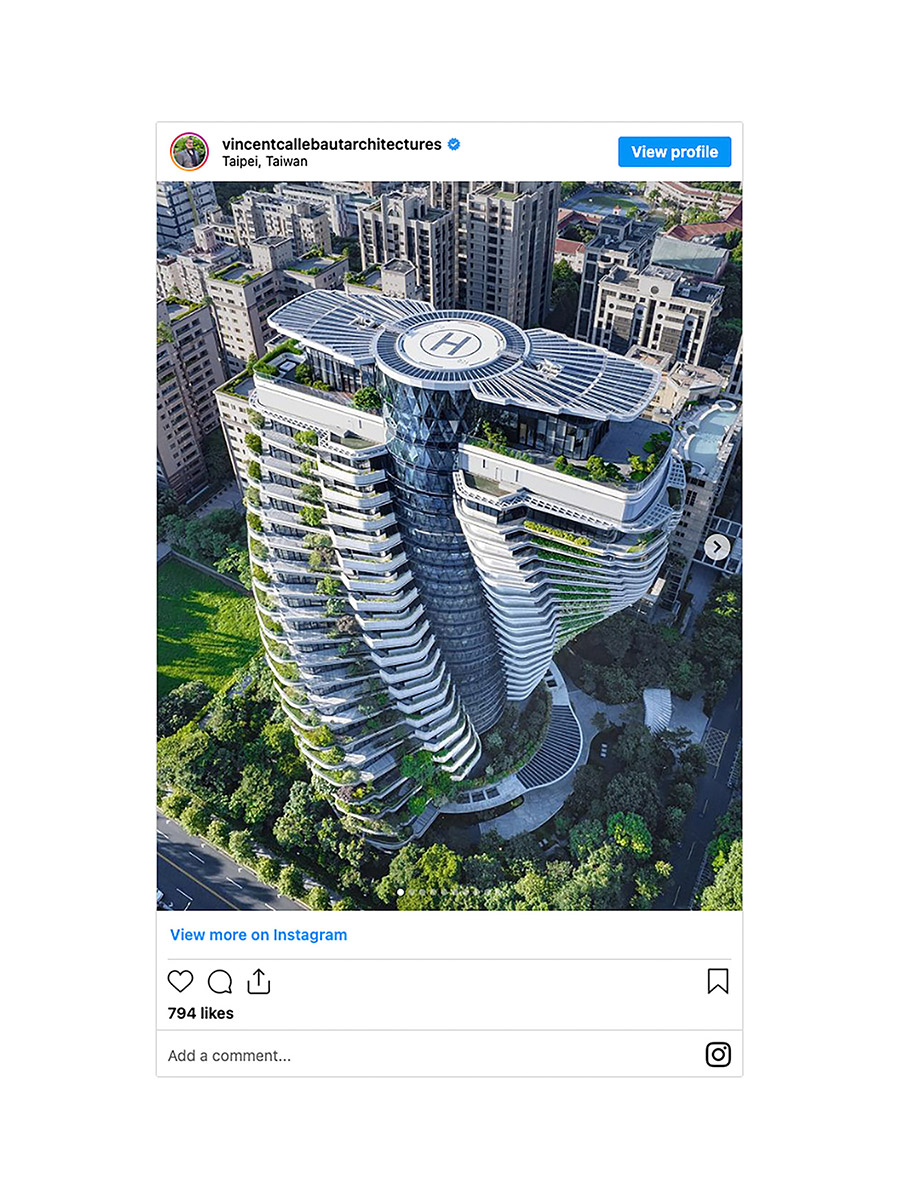

Vincent Callebaut

Garden towers are also taking root in Taiwan, where the Belgian-born, Paris-based architect Vincent Callebaut has broken out of his conceptual straitjacket and entered reality. Callebaut’s green architecture vision typically pairs elaborate organic forms with a surface coating of dense vegetation. Over the past decade, he has proposed a lily-like floating “ecopolis for climate refuges”, a futuristic cluster of algae farms designed to recycle carbon dioxide and a vast array of towers shaped like stacks of balanced pebbles for a Shenzhen development.

In Taiwan, Callebaut’s Taipei project, the Tao Zhu Yin Yuan Tower, is twisted around a central core, allowing the generous balconies to overflow with hanging vegetation. The architect — prolific, outspoken and deeply optimistic about the role of architecture in transforming our environments for the better — designed the building to absorb up to 130 tons of carbon dioxide every year, a major bonus in the congested city. After 11 years of construction, the project was concluded in 2021 and is now a global benchmark for the future of green architecture.

Belgian Vincent Callebaud’s ambitious eco-neighbourhood in his native city of Brussels with three sky villas

Other Callebaut projects include the “L’Écume des Ondes” project, also known as the Foam of Waves, which has received its building permit and is set to become a remarkable example of green architecture in 2025. Situated in the Ancient National Thermal Baths of Aix-les-Bains, the project aims to reveal the intrinsic heritage of the site while embracing contemporary sustainable design. With a focus on sustainable housing, the project features two buildings that are designed to resemble vertical forests, with landscaped balconies creating a striking visual effect. Furthermore, the technical innovations incorporated in the project, such as building a carbo-absorbent forest and filtering water, align with the objectives of RT 2020 and aim to obtain the NF Habitat HQE label. The Foam of Waves truly represents a harmonious blend of heritage preservation and innovative green architecture.

These are ambitious projects, but the fundamentals that underpin Callebaut’s vision are hard to fault: high density, high technology with minimal impact on their surroundings (at least in terms of energy consumption). And this organic approach cloaks the sheer scale and impact of modern urban development.

For the most part, green architecture continues to emerge gradually, rather like saplings and shoots coming up through the cracks in a pavement. The world’s cities won’t go green overnight, especially not to the scale, scope and vision of architects like Callebaut.

Go back

Go back